How to Edit and Proofread Content

Use Effective Time Management & Beware of the Grammar Check Trap

Before you turn in any manuscript, you must take the time to proofread and edit the document carefully. Merely using Spelling and Grammar Check through Microsoft Word will not get the job done. Instead of rushing to proofread ten minutes before the paper is due, you need to take proofreading seriously and allot a substantial amount of time for the activity.

Once you've finished writing a manuscript, it's a good idea to "let the paper rest" for a while and come back to proofread it later. It's easier to see grammatical and stylistic glitches if the paper isn't fresh in your mind. Focus on the style, grammar, and spelling in every single sentence.If you only rely on Spelling and Grammar Check, it's highly probable that you'll still have many errors in your paper. Spellcheckers miss all kinds of usage errors (they're vs. there vs. their, for example) and other grammatical problems. These simple errors hurt the readability of the document by distracting your reader, which in turn damages the paper's credibility.

Read the Paper Out Loud

Reading a document aloud is a common technique used by both beginning and professional writers. Reading a paper out loud slowly will help you catch phrases that don't "sound right" and will let you focus on what's there on the paper, not what you meant to say. You can also use any program that reads aloud; this is what works best for me.

Read the Paper Backwards

Another helpful technique used by professional writers is reading a paper backward. What this means is that a writer starts by proofreading the last sentence. You read that sentence, making sure there were no misspellings or mechanical errors. Then you move on to the next-to-last sentence, and so on. Writers do this because reading a document backwards takes it out of context. You're able to isolate the sentences and their grammatical issues by reading it backwards.

Read the Paper Out Loud and Backwards

Use this hybrid method by incorporating both techniques provided above.

Use the Pencil or Ruler Method

Some writers use a pencil or ruler as a guide to focus on each individual sentence as they proofread. This technique stops a person from getting ahead and helps one concentrate on the sentence at hand.

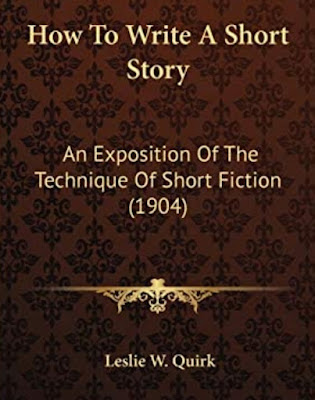

Use the Each Sentence As Its Own Paragraph Method

One helpful method for focusing on both sentence variety in your writing and grammatical/mechanical errors within paragraphs is to reformat your document by making each sentence its own paragraph. Instead of using double spacing with sizeable paragraphs, convert your document to single spacing to examine each sentence in a line-by-line fashion. You format the paper by taking every sentence and placing it on one line by itself to look for grammatical errors, unnecessary repetition, and places where you can vary the lengths and types of sentences used in your prose. Since sentence variety ~ using different types and varying lengths of sentences ~ creates strong cohesion (a.k.a. "flow"), writers use this method to look for ways to make the document stylistically stronger.

*For example, if I were to present the paragraph above, here is what it would look like using the "each sentence as its own paragraph" method:

One helpful method for focusing on both sentence variety in your writing and grammatical or mechanical errors within paragraphs is to reformat your document by making each sentence its own paragraph. Instead of using double spacing with sizeable paragraphs, convert your document to single spacing to examine each sentence in a line-by-line fashion. You format the paper by taking every sentence and placing it on one line by itself to look for grammatical errors, unnecessary repetition, and places where you can vary the lengths and types of sentences used in your prose. Since sentence variety (using different types and varying lengths of sentences) creates strong cohesion (a.k.a. "flow"), writers use this method to look for ways to make the document stylistically stronger.

*For example, if I were to present the paragraph above, here is what it would look like using the "each sentence as its own paragraph" method:

One helpful method for focusing on both sentence variety in your writing and grammatical or mechanical errors within paragraphs is to reformat your document by making each sentence its own paragraph. Instead of using double spacing with sizeable paragraphs, convert your document to single spacing to examine each sentence in a line-by-line fashion. You format the paper by taking every sentence and placing it on one line by itself to look for grammatical errors, unnecessary repetition, and places where you can vary the lengths and types of sentences used in your prose.

Since sentence variety (using different types and varying lengths of sentences) creates strong cohesion (a.k.a. "flow"), writers use this method to look for ways to make the document stylistically stronger.

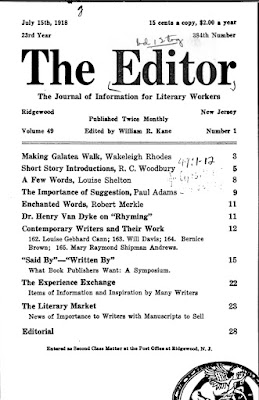

This Article's Sponsor

I don't know what I would do without ProWritingAid to check my writing. It gives me so much more confidence in everything I write. Want to see what I mean? Try it for yourself.